Building Beautiful Homes

The Next Phase of California’s Pro-Housing Reforms

By Eduardo Mendoza

California is finally making it easier to build more housing – but the next fight is whether people like what gets built. Ugly and cheap-looking buildings can turn housing-neutral voters into opponents. The fix isn’t more design review meetings or process – it’s streamlined rules and tools: modernized building codes that make smaller, more varied buildings feasible. Combined with ready-to-use pattern book templates and clear design standards, our cities can deliver durable, attractive buildings and greener streetscapes while keeping permitting fast and predictable.

California has spent over a decade trying to make it legal and feasible to build more housing: limiting local veto points, rewriting zoning rules, and pushing permitting systems to say “yes”. It’s working.

However, there’s a missing piece that housing policy still treats like an afterthought: how buildings look, function, and feel. If the last decade’s question was: can we build new housing? The next decade’s question is what that housing looks like, and how it works? People don’t experience “housing policy” in the abstract. They experience it as streets and buildings: what they walk past, what they see from the bus stop, what quietly remakes their neighborhood.

This matters for politics. Some people will fight “density” no matter what, but a larger group, something I refer to as housing-agnostic voters, can be pushed into support or opposition by a reaction: “this looks good”, or “this looks bad”. New research suggests “ugly building” reactions can predict opposition as strongly as many of the usual explanations for anti-development sentiment. (Broockman–Elmendorf–Kalla 2025).

The good news is that solving this challenge isn’t a mystery, and it doesn’t require a new bureaucracy. It’s a political problem, but also a real policy opportunity: we already know which design cues people respond to, and we can bake them into objective frameworks and rules that are easy to approve and easy to like. That’s the next phase of Yes in my Backyard: beautiful housing as the default.

Regulating the wrong design levers

Our current objective design standard paradigm is built on the wrong mental model of how people perceive buildings. It assumes you can “design away” ugliness by chopping a façade into smaller pieces: more stepbacks, pop-outs, jagged rooflines, and plane changes, so the building feels “less big.” But contextual-design research shows why this keeps disappointing: people don’t evaluate a building the way a zoning diagram does. They evaluate it the way they experience a street, pattern, coherence, and comfort at a glance. When the underlying form and materials feel cheap or incoherent, extra façade break-ups read as fussiness, not beauty, and it often does little to change minds.

The evidence points to a more durable playbook: pattern, materials, and coherence over fragmentation. Public preference shifts most when a building fits its surroundings, has a legible style, shows real craft and durable detail, and sits in a generous streetscape of trees and greenery. Those are cues people can actually read, and they scale from one project to an entire neighborhood without requiring a bespoke design fight every time. That’s the future of beautiful housing: streets that feel intentional, green, and coherent, because the rules target what people reliably respond to. (Stamps 2014; Stamps 1994; Nasar & Stamps 2008).

The hidden cost: risk and climate fragility

Cities have forced façade complexity into our building codes, which is sold as a shortcut to beauty: add stepbacks, pop-outs, and lots of façade breaks, then the building will feel “better designed.” In practice, the wide variety of façade requirements often does the opposite: the added joints, penetrations, and material transitions lead to higher construction risk, harder waterproofing, and more defect exposure without the resounding public support that would make the trade-off worth it. In a state where housing is already expensive to build, we’re effectively adding cost and fragility in the name of design, without strong evidence that the policy reliably produces buildings people actually like. (VanDemark-Clevenger-Click 2021).

Fragility isn’t only a construction risk; it’s a climate risk too. Electric cars and better energy policy help, but the biggest and most reliable climate wins come from neighborhoods where people can walk to daily needs, because pleasant and safe streets mean fewer car trips. The same resilience logic applies to buildings: the strongest designs stay comfortable in heat with fewer points of failure.

Beauty and performance don’t have to be in tension. The things people consistently respond to, coherent style, real detail, good materials, and greenery, can be delivered in simpler, more durable building forms. Changing the paradigm of what constitutes “beauty” matters more as California gets hotter. Buildings that rely on complex envelopes and perfectly functioning mechanical systems are more brittle during heat waves and grid stress. A truly modern design standard should reward the opposite: durable assemblies, shade, passive comfort strategies where feasible, and streetscapes that are genuinely pleasant to live on.

If design reviews were reliably producing that outcome, you could argue the process is worth it. However, the research suggests that discretionary committees and “expert” review often don’t resonate with what the broader public ends up preferring, while straightforward pre-construction image testing of building forms and styles predicts public reaction much more closely. (Stamps 2014).

So the answer isn’t a statewide beauty board, or more processes that add steps, regulation, and time. It’s by-right approval (if you meet the rules, you get approved) with clear, bold evidence-based design rules: evidence-aligned, objective rules that create buildings and streets people actually find beautiful, while reducing cost, risk, and climate fragility.

What California can do now

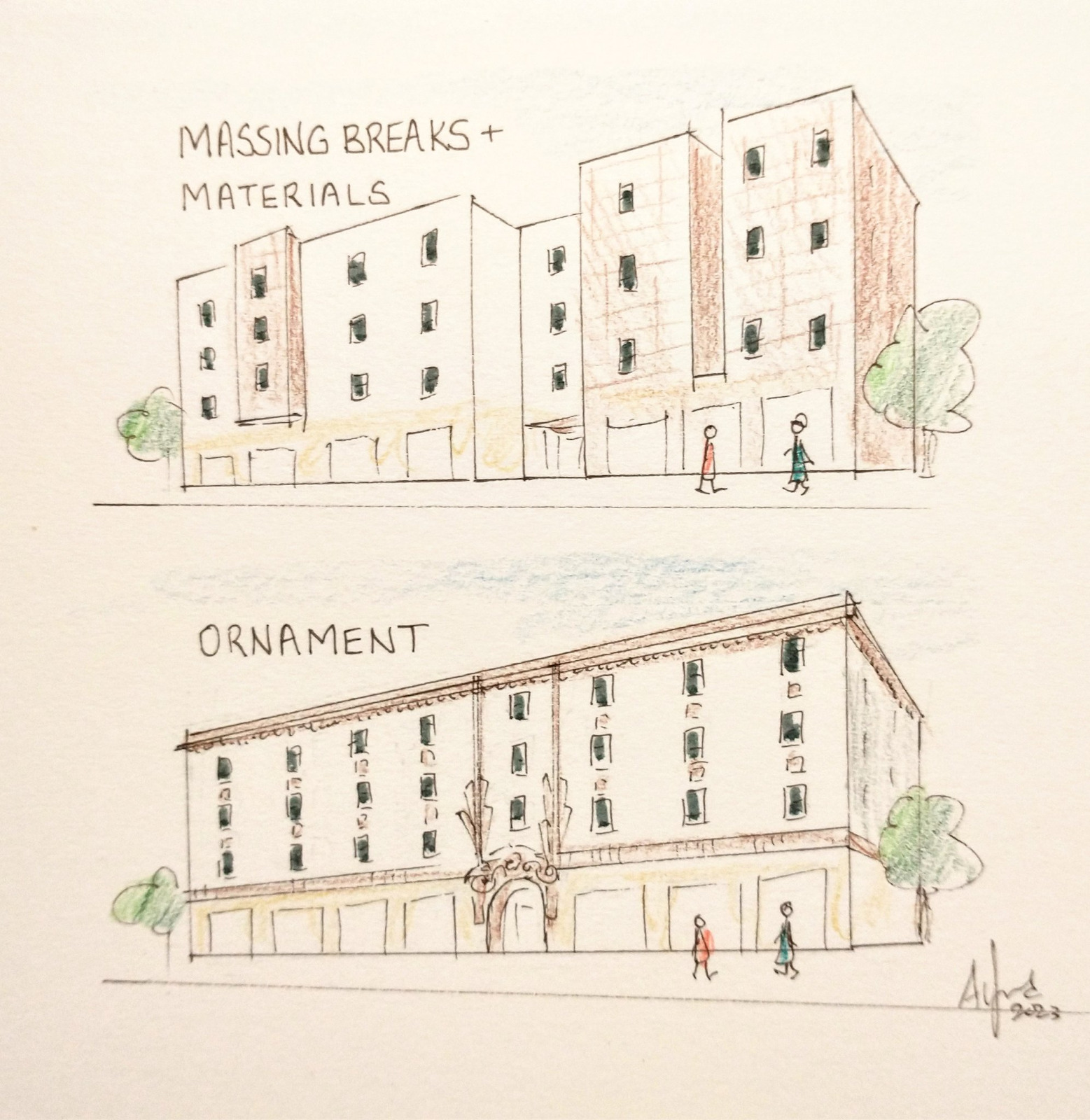

- Add an “ornamental façade alternative” to the state Objective Design Standard model.

Many local Objective Design Standard codes demand heavy articulation and multiple cladding changes. The evidence suggests those moves have limited payoff compared to coherent style, material quality cues, greenery, and visible detail. (Stamps 2014; Nasar & Stamps 2008).

Fix: Update the California Department of Housing and Community Development’s model Objective Design Standards to give projects a clean choice: (A) comply with conventional massing/articulation rules, or (B) use a simpler envelope and meet a measurable threshold of real ornament (projections/recesses, columns/bands/cornices/fins, tile or relief work, murals), with minimum depth and material standards. Fewer joints and penetrations mean fewer leaks; visible craft improves public reception. This policy concept has been introduced in the 2023 North Berkeley Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) Objective Design Standards and can be expanded statewide.

- Build a statewide pattern book framework so the best designs are encouraged and streamlined.

For decades, “better design” usually meant design review: a meeting, a debate, a negotiation, and often a delay. California has been moving away from that world. In 2019, SB 330 (the Housing Crisis Act) limited cities’ ability to use discretionary approvals to delay or downsize housing, so in effect, aesthetics can’t be a bargaining chip or delay tactic anymore. If a city wants to shape what gets built, it needs to put its standards in writing, clear, measurable, yes-or-no.

That’s the right direction. However, it also creates inequity: cities with money can write thoughtful standards, and cities without money either copy-paste weak templates or skip design policy altogether. The result is uneven quality and an avoidable hit to public confidence in new housing development.

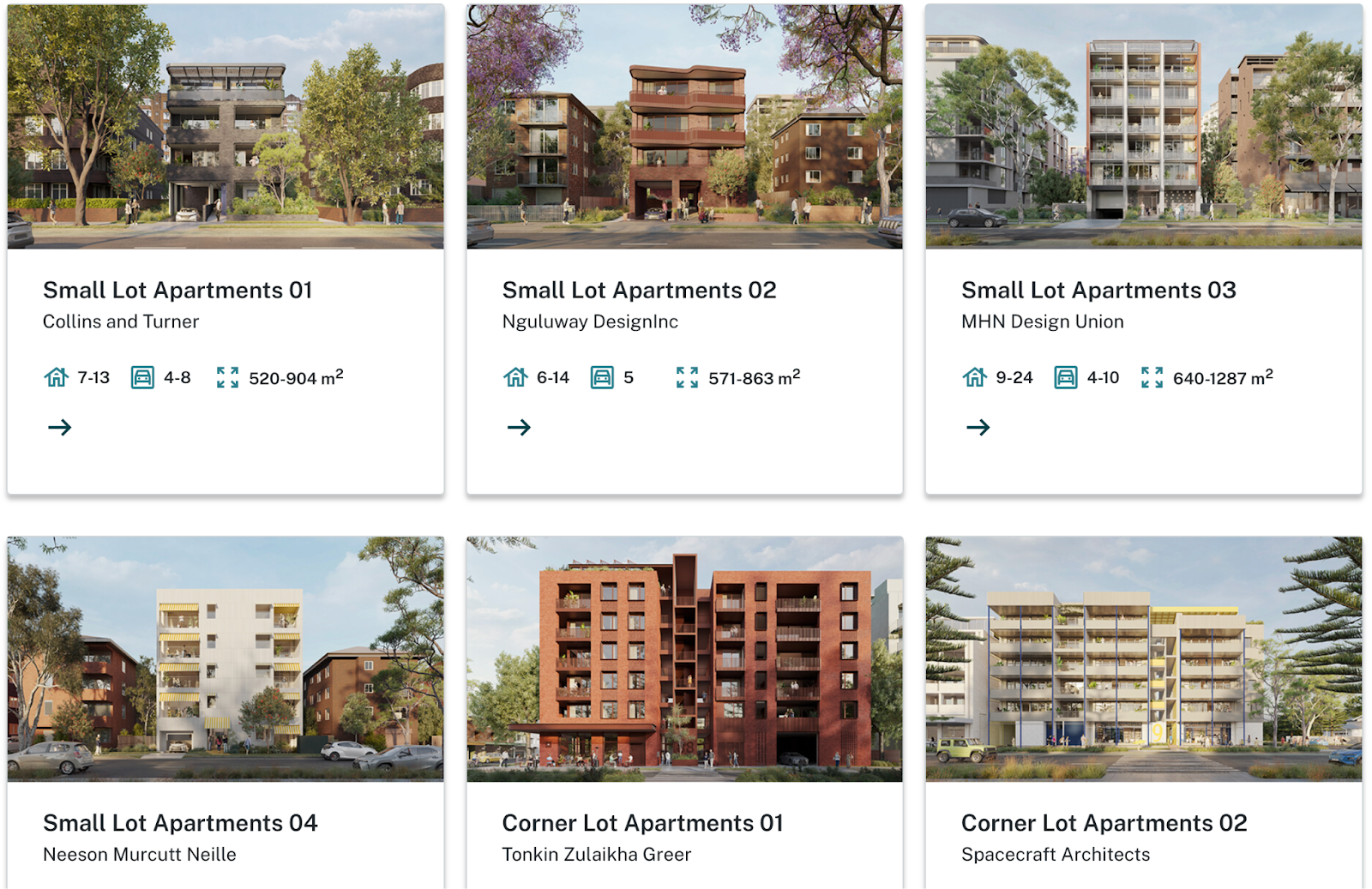

Fix: Instead of asking every jurisdiction to reinvent the wheel, California can provide the framework necessary to create pre-approved, objective design “families” that cities can adopt quickly. A state-supported pattern book – with a variety of vetted building designs submitted by designers across California and the world – that jurisdictions can adopt. Designs can include building-type templates (courtyard housing, small-lot multiplexes, mid-rise forms) and “style families” written as checklists (window proportions, balcony projections, cornice depth ranges, material palettes, tree spacing, façade rhythm, along with the strongest energy efficiency standards) that comply with building code, eliminating the need for discretionary approvals.

Other jurisdictions already do this. New South Wales, Australia, recently launched a housing pattern book that offers pre-vetted, ready-to-use designs for mid-rise buildings that can move through approvals quickly. The California catalogue will be expandable: cities and architects can submit designs/patterns from successfully built projects from across California to be converted into new pattern-book families. The library grows over time and becomes a reliable resource for cities or specific areas that wish to adhere to approved design standards.

- Modernize building codes so we can build compact, elegant mid-rise housing.

If California wants more European-feeling mid-rise development with courtyards, better daylight, shade, and balconies, it has to keep modernizing the code environment that shapes building form. Too many building, electrical, and fire rules (in California and across the U.S.) aren’t aligned with the best global practices for safe, livable mid-rise housing. The result is less freedom to build the buildings people actually like: bright cross-ventilated homes, true courtyard buildings, and mixed-use ground floors. All these requirements – egress, stairs, corridor, and elevator – often make projects bulkier and require much bigger lots, limiting where we can build new housing and who has access to the capital to build multi-family housing. The effect is that before design is even on the table, the web of building code regulations denies light, proportion, street connections, courtyards, greenspace – everything that makes buildings feel humane.

Fix: Passing single-stair reforms and elevator reforms makes smaller mid-rise buildings possible, which fit on smaller lots, can be nestled into existing buildings, add variety to the streetscape, and reduce the pressure for larger, monotonous developments.

Additionally, much of our building code has become overly prescriptive, leaving less room for design to do what it does best: create resilient buildings that stay comfortable through courtyards, shading, operable windows, cross-breezes, and green space that cools naturally, reducing energy dependence in the process. We should shift toward codes that focus on outcomes, expanding performance-based pathways that reward passive comfort instead of steering every project toward an “always-air-conditioned box”. \

- Help cities translate state upzoning into coherent, lovable neighborhoods.

In the last five years, California has upzoned big parts of its cities, unlocking multi-family housing in places that used to allow little more than single-family homes. The state has told cities “you need to allow more housing,” but it hasn’t given them a clear playbook for what that new growth should look and feel like.

Fix: State housing laws are reshaping station areas and corridors. Pair implementation (Abundant and Affordable Homes Near Transit Act SB 79/ Starter Home Revitalization Act SB 1123/ Affordable Housing and High Road Jobs Act AB 2011 and related reforms) with ready-to-use tools: ornament alternatives, building design/envelope standards, tree/streetscape standards, and the pattern books discussed earlier. (Stamps 2014).

Why this is the right bet

Aesthetics matter to people, and it shows up in the politics of housing in measurable ways. The evidence is remarkably consistent: people respond most to coherent style, visible detail, trees and greenery, and designs that fit their surroundings, and when those cues are present, support for new housing rises. (Broockman–Elmendorf–Kalla 2025; Stamps 2014).

California’s housing politics are not just about maxing out the units one can build; they’re about legitimacy. The best way to protect the pro-housing movement is to make beautiful housing the default outcome, through objective rules aligned with what people reliably prefer, without rebuilding the discretionary veto machine that created the shortage.

Eduardo Mendoza is a policy analyst, researcher, demographer, and housing advocate who spends a lot of time thinking about how rules, maps, and building codes shape who gets to live where. He is a Research Associate with California YIMBY and the Metropolitan Abundance Project (MAP), working on state and local reforms to make it easier to build abundant, beautiful, and affordable homes. His work and ideas have been featured in outlets such as HUD’s Cityscape Journal, the Los Angeles Times, and Slate Magazine.