Water, Water Everywhere? Depends on Where You Look

Can the San Francisco Bay Area grow sustainably with a limited water supply? A new study by SPUR and the Pacific Institute shows that more dense development in urban areas can ensure that the region’s growing population does not add excess water demand to California’s drought-stricken water infrastructure.

Key takeaways:

- By 2070, the Bay Area can add 2.1 million jobs, 6.8 million people and 2.2 million homes by 2070 without straining the water supply.

- This projected population growth can offset all of its increased water consumption with efficiency gains through infrastructure improvements and urban density.

- By implementing even more ambitious plans (there are 18 recommendations in total), the Bay Area could even grow more while using less water than today.

California is thirsty. In “Water for a Growing Bay Area,” Feinstein & Thebo (2021) observe that years of drought exacerbated by climate change have enabled some growth-averse jurisdictions to enact moratoria on new housing development due to impending water shortages. In some cases, the authors note, short-term fears may be valid, but in the long-term, simply turning off the tap on growth isn’t a sustainable solution.

While water scarcity can and should spell bad news for suburban lawn enthusiasts, dense urban infill development is precisely what’s needed for the Bay Area to develop more resilient water infrastructure (to say nothing of its general effectiveness in fighting climate change).

In some ways, the solution has been clear for some time. After peaking in the 1980s, water demand has largely decoupled from population growth. The average California household now uses 40% less water than half a century ago. A growing Bay Area needs to keep going in this direction.

The report focuses on urban water systems, largely because the agricultural sector is already projected to steeply cut its water use thanks to the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act of 2014, while a similarly comprehensive policy for reducing urban water consumption is not in place.

By modeling six possible scenarios of the next half-century, Feinstein & Thebo predict “that the Bay Area’s applied water use in 2070 could be 40% lower if the region pursued efficiency measures and compact land growth instead of a business-as-usual approach to growth with little increase in efficiency.” Applied water reduction scenarios for the state’s agricultural sector, meanwhile, range from 2% to 22% in a varied body of literature.

In technical jargon, “applied water use” is all water used in the system, including water consumed by crops that cannot be immediately reused, and water that may percolate to a nearby reservoir and be reused in the near future.

To ensure long-term water sustainability, the report delivers 18 policy recommendations summed up under three broad categories:

- Efficiency and conservation

- Compact land-use reform to enable more multifamily housing

- Regional cooperation, alternative water sources, and returning water to wildlife

The first is pretty straightforward: conserve water by taking shorter showers, and use water more efficiently with a low-flow showerhead. But how can this dynamic be applied at a broader scale? That’s where land use comes in.

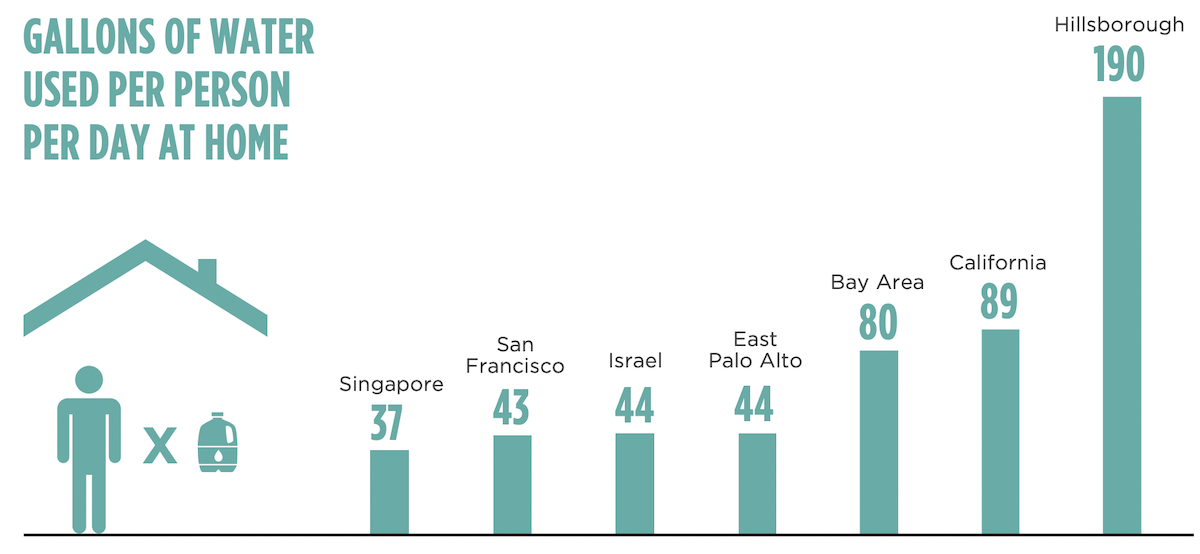

To get a sense of the water consumption that could be saved with more dense urban living, this chart from the report neatly sums up how wasteful the average household in suburban jurisdictions such as Hillsborough can be, compared to the urban core of San Francisco:

SPUR chart

Urban infill reduces per capita water consumption in several ways: (1) by reducing water per capita used for landscaping; (2) building housing in areas with existing sewer lines results in less new water demand than adding water supply to exurban land without water infrastructure; and (3) new buildings adhere to modern building codes with more efficient plumbing and fewer leaks. This has serious consequences for housing policy, given that the low-income city of East Palo Alto had to establish a building moratorium in 2016 and could only permit new construction after Mountain View and Palo Alto agreed to share water with their struggling, poorer neighbor. More recently, the Marin Municipal Water District is considering a temporary ban on new lines that could prevent new urban infill in San Rafael, with priority development areas near transit and jobs.

There are two basic scenarios that SPUR envisions for the future of the Bay Area: business as usual, and a YIMBY future with more urban infill housing near transit. In the latter scenario, a similar population consumes the same amount of water and enjoys 800,000 more new homes near jobs and transit than in the “business as usual” scenario with more suburban sprawl and worsening affordability.

“Compared to sprawl growth, compact growth doesn’t decrease total water use, but it decreases per capita consumption dramatically,” Feinstein & Thebo explain. “In the compact growth scenarios, the region is able to fully address housing demand and yet use about the same amount of water as in the sprawl scenarios.”

However, efficiency likely won’t be enough. As the authors observe, “growth will outstrip the potential to offset demand with local conservation and efficiency. Meeting the demand for every part of the Bay Area will require transferring water within the region or identifying alternative supplies.”

Other recommended strategies include “water transfers” in which water utilities form long-term agreements to share resources (such as the recent agreement between East Palo Alto, Mountain View, and Palo Alto) and investing in alternative water sources such as recycling, stormwater capture and desalination. Nevertheless, the first step toward a more resilient water system in the future depends on making more sustainable choices about how we use land today.