Elements of Zoning

What zoning is, and what zoning is not.

What is zoning?

Zoning is the primary tool U.S. cities use to designate how a specific plot of land can be used and how intensely it can be developed. Zoning regulates both function and form.

In most cities, the zoning code defines several types of zones or districts, and assigns all parcels to one of those zone types. Each zone type allows one or more land uses, such some areas might be zoned for residential uses and others for commercial or industrial uses. Mixed-use zones allow multiple uses on one parcel or — making possible, for example, the development of a residential apartment complex with retail space on the ground floor.

Zones vary in their restrictiveness. A restrictive residential zone might permit only single-family detached homes at a density of one home per acre. Elsewhere, a residential zone might permit the creation of duplexes, triplexes, and other multifamily buildings.

What isn’t zoning?

Rules governing health and safety issues — like whether a building needs emergency exits or whether you can put a toxic waste dump next to a school — are covered by sections of the municipal code other than the zoning code. A city can significantly alter its zoning without endangering people or harming the environment.

Additionally, you may have heard about general plans (or comprehensive plans), which all cities, counties, and towns in California are required to have. The general plan is a high-level framework intended to guide a city’s physical development in the medium- to long-term, based on the community’s goals. The zoning code, on the other hand, is the detailed blueprint that planners follow when making decisions. Cities are supposed to ensure consistency between their general plan and zoning ordinance.

How does zoning regulate form and density?

In addition to specifying what a given lot can be used for, zoning codes prescribe the physical characteristics of buildings, lots, and public spaces. In other words, zoning regulates a parcel’s building envelope.

A building envelope is the three-dimensional space within which a building must fit, taking into account all local zoning regulations. Visualize a big, invisible cube, where the cube is as tall as the maximum height allowed on that parcel and the sides of the cube are defined by the minimum required setbacks.

A lot of different variables help to determine the building envelope. Let’s consider them below.

Height

This one is pretty straightforward. A city’s zoning code sets the maximum allowing building height in each zone. In downtown or commercial zones, the height limit might be quite high to allow for tall apartments or office buildings. In areas that are zoned for single-family homes, the height limit might be relatively low—say, 25 or 30 feet.

Setbacks

Setbacks refer to the minimum amount of distance required between a structure and the lot’s property line. Typically measured in feet, minimum setbacks often vary between the front, side, and back edges of the lot.

Lot Size

Lot size is, well, how big a lot can be. It usually refers to the minimum or maximum size a parcel can be within a given zone. In residential zones, minimum lot sizes can range from a couple thousand square feet to multiple acres.

Lot Coverage

Lot coverage dictates how much of a given parcel’s area can be covered by structures. It’s measured as a ratio or decimal. For example, if a parcel has a maximum lot coverage of 0.2, it means that the base (or footprint) of the building can take up 20% of the lot, and the rest of the lot’s area would be covered by lawn or pavement.

Floor Area Ratio

This one is less intuitive. Floor area ratio (FAR) is the ratio of a building’s total floor area (across all floors) relative to the area of the lot the building is built on. FAR aims to quantify intensity of development. Given its lot size, how big does the building feel?

FAR is calculated by dividing the total area of the building by the lot’s area. An FAR of 0.5 means that a building’s floor area may be no greater than half the lot area. An FAR of 1.0 would mean that the floor area of that building may equal the lot area; assuming there are setbacks, this would imply that the building is more than one story. An FAR of 5.0 means that the building’s floor area may be up to five times as large as the lot area and, probably, more than five stories tall.

Density

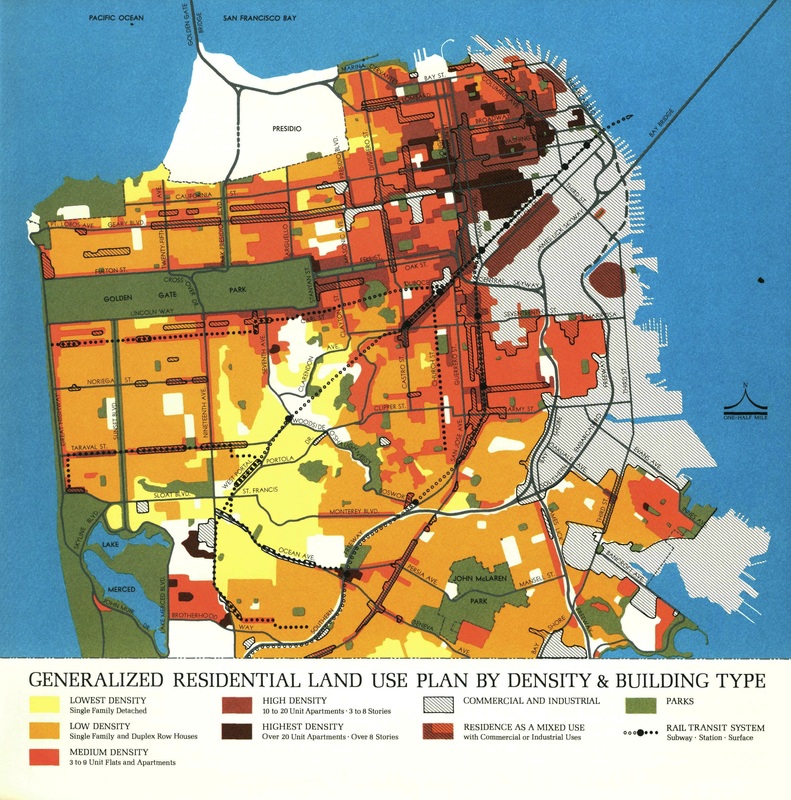

Density refers to the amount or intensity of development that is permitted on a given parcel. In residential zones, density is typically measured as the number of dwelling units per acre, though density can also be measured as the number of structures or buildings allowed per acre. Many jurisdictions regulate the level of density allowed in different zones in a practice known as “density zoning.” Cities commonly designate some residential zones as low-density (e.g. zoned for single-family homes) and others as high-density (e.g. where larger multifamily developments are allowed).

This all sounds pretty complex. Why do cities impose rules in all these different categories?

Cities want to control what can be built where. In many ways, this makes sense. A key benefit of zoning is the ability to separate incompatible land uses, such as residential areas and heavy industrial uses. (Though, as mentioned above, there are plenty of non-zoning ways to keep polluting industries out of neighborhoods where people live.)

Municipalities also want to regulate how their city looks and maintain some level of cohesion. For this reason, a city might regulate height so that there is not a 20-story building next to one-story houses. Cities might also introduce some regulations for the betterment of the community, such as requiring setbacks to accommodate sidewalks and curb cuts.

It is important to note that cities have historically used zoning to institute residential segregation and regulate land in a way that disproportionately harms people of color and poor people. When many cities—including Berkeley and San Francisco in California—first adopted zoning, it was with the express intent of keeping non-white people out of majority-white neighborhoods by outlawing the development of lower-cost housing in those areas.

What are the real-world consequences of how U.S. cities do zoning?

Restrictive zoning effectively makes it illegal to build more than a certain amount of housing in a particular neighborhood, city, or metropolitan area. When the population of a particular area starts to outgrow the limits imposed by its zoning code, the result is usually a housing shortage and a consequent affordability crisis.

That’s what happened in California, where decades of underbuilding led to a severe housing and homelessness crisis. For a particularly stark illustration of how this happened, consider that Los Angeles spent the years between 1960 and 1980 aggressively cutting its zoned capacity. In effect, one generation of Angelenos hamstrung successive generations’ ability to accommodate both newer and older residents. This dynamic has played out across the United States.

In addition, the explicitly racist zoning policies of the past continue to exacerbate racial inequality today.

So what should policymakers do?

Local policymakers should “upzone,” or increase an area’s allowable density, especially in areas close to public transit or other amenities. This is essential to make up for downzonings that have occurred in the past.

Where local policymakers are unwilling or unable to enact the necessary upzonings, state lawmakers should do it for them. For example, California’s AB 2011 (2022) allows the development of affordable and mixed-income housing in many areas that were previously zoned exclusively for commercial use. Other states, notably Montana, have also preempted local restrictive zoning rules.

Okay, but does upzoning really work?

It really does. Some of the best evidence we have of zoning reform’s effectiveness comes from Auckland, New Zealand, which passed a significant upzoning in 2016. Since then, rents in the city have declined by more than 22-35 percent for three-bedroom units, according to one study. If the city had maintained its prior zoning map, the study estimates, the rent for a three-bedroom apartment would be 50 percent higher.

Zoning reform on its own won’t address every element of the housing crisis. But it’s a critical and necessary step toward broad-based affordability.

Where can I go to learn more?

Here are some resources if you’d like to know more:

- Arbitrary Lines: How Zoning Broke the American City and How to Fix It

- The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America

- The Effect of Land Use Regulation on Housing Prices: Theory and Evidence from California

- Zoning and the Cost of Housing: Evidence from Silicon Valley, Greater New Haven, and Greater Austin

- 3 Zoning Changes That Make Residential Neighborhoods More Affordable

This primer was prepared by Emily Jacobson and Spencer Richard.