LA’s Apartment Bans Promote Segregation – and High Housing Costs

Single-Family Zoning in Greater Los Angeles, a new study by Menendian et al (2022) at UC Berkeley’s Othering and Belonging Institute, examines new evidence on the relationships between exclusionary zoning, household income, home value, educational attainment, educational performance, and environmental health.

Key takeaways:

- Local jurisdictions in the LA-metro region with a greater share of land zoned single-unit only were correlated with higher household income and higher home prices, effectively excluding lower-income households.

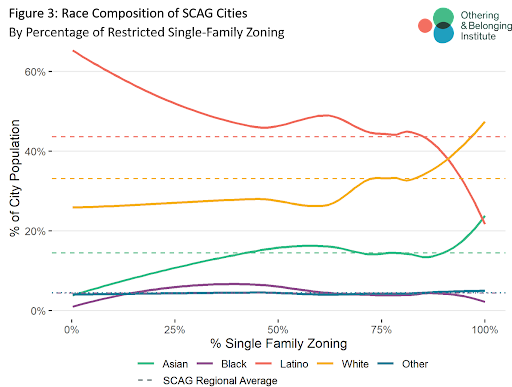

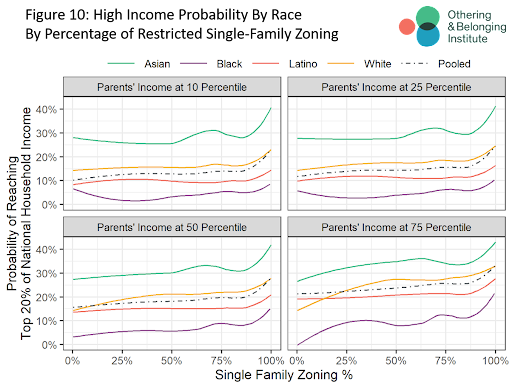

- Single-unit zoning has an intersectional and generational impact on race and class exclusion. Higher shares of single-unit zoning were associated with whiter populations and a smaller Latino population; at the same time, “upward mobility for all racial groups appears to be correlated with the proportion of single-family zoning.”

- Exclusionary zoning is also associated with better educational outcomes, environmental quality and health.

Menendian et al follow up on their groundbreaking study of the San Francisco Bay Area with a similar data analysis of land use policy and inequality in the Greater Los Angeles Area. This region covers municipalities in the Southern California Association of Governments (SCAG), with 191 unique zoning codes. As the authors explain, data in this study supports the hypothesis “that restrictive zoning is a mechanism of opportunity hoarding, the channeling of critical resources and amenities into some communities and the denial of those assets and resources to other communities. “

First, the evidence is clear on class and race segregation: “the more single-family-only zoning, the whiter the jurisdiction and the proportion of Latinos declines relative to the regional population,” Menendian et al report.

On wealth-based exclusion, the evidence is even more stark. The authors report: “Household incomes increase as the percentage of single-family-only zoning rises,” as well as home prices.

Indeed, the handful of municipalities with median household incomes above $150,000 per year had nearly 100% of their residential land zoned exclusively for single-unit housing. Similarly, “it is notable that the average of median home values are more than twice as great in jurisdictions with more than 90 percent single-family-only residentially zoned areas ($811,492) compared to those with less than 10 percent ($405,875).”

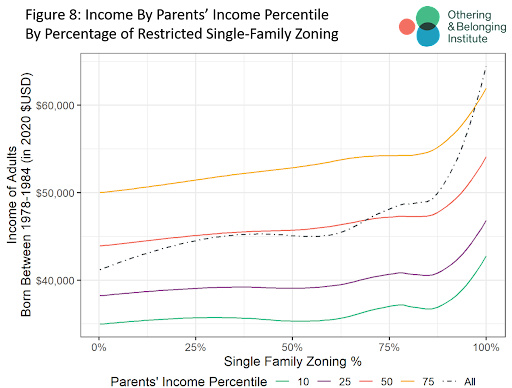

Further deepening the economic inequality on a generational scale, there is also a striking, direct correlation between single unit zoning and economic mobility. This economic mobility is also not distributed equitably for Black and Latino households. Menendian et al examine this by comparing census data on LA residents’ lifetime earnings with that of their parents.

These patterns are also borne out in environmental harms and educational inequities. Menendian et al observe that the evidence shows “jurisdictions with more restrictive zoning having higher rates of high school graduation and a greater concentration of college graduates as well as higher proficiency scores.”

Similar inequities are seen in the quality of drinking water and risk of lead exposure. The authors note with alarm given the directly lethal implications: “there is an almost perfectly linear inverse relationship between the lead levels and percentage of single-family zoning.”

While these observed correlations are not empirically causal evidence, this data gets at an even deeper issue: the causal mechanisms of structural inequality can cut both ways. “Restrictive zoning may spur high-income people to cluster by providing a mechanism by which they can leverage the powers and prerogatives of local government to hoard resources for themselves and their children,” Menendian et al suggest. “These investments and policy preferences tend to result in better outcomes for their children, which, in turn, perpetuates the cycle of advantage.”