Homelessness is on the Rise. Will Sacramento Step Up with Reforms?

Sign up for the California YIMBY Newsletter!

As the number of people experiencing homelessness in California continues to grow, our elected leaders in Sacramento should be forced to answer one vital question: At what stage will the housing crisis and rising homelessness spur them to act?

The recent “point in time” homelessness survey, conducted by cities across the state, showed the stark consequences of our collective failure to reform our outdated housing policies: California’s homeless population — which includes over 130,000 people — grew by double-digits in almost every city in the state; in some cases, as much as 43% year-on-year.

The ongoing growth in homelessness has given California the ignominious distinction of having nearly 25% of all people experiencing homelessness in the United States — despite our state only having 15% of the population.

Fully 69% of California’s homeless are without any form of shelter, which means they live on the streets or in tents. And contrary to oft-repeated myths that the homeless are from out-of-state, the majority of homeless in California were living in California when they became homeless.

More importantly, people experiencing homelessness are our neighbors and friends. They’re our relatives and coworkers. We have a moral obligation to help ensure they have safe, secure, affordable housing. Their current plight — living in tents, in cars, and under freeways, and often dying on our streets — is unacceptable.

Statewide Homeless Stats Top CA Cities, Survey 20191-year count = count conducted annually

*Numbers are likely an under-count to survey limitations |

There’s No Silver Bullet

Solving homelessness requires a multi-pronged approach: building more housing in general to reduce market pressures; providing housing subsidies for very low-income people; funding and building homeless navigation centers in accessible locations; and increased funding for permanent, supportive housing.

But there’s a counter-intuitive solution that’s just as important: We also need to make sure we’re building enough housing for moderate- and high-income earners, to reduce the pressure on our existing affordable housing stock. Building market-rate housing to keep pace with job growth — including growth in high-paying jobs — is a must-have strategy to slow and, ideally halt, the trend of evictions, house-flipping, gentrification, and ever-rising rents.

As we know, implementing these solutions are difficult. For one, the state has never provided — and may never be able to produce — sufficient financing for 100% affordable housing for people experiencing homelessness or at risk of homelessness. There’s also the issue of legality: Due to Article 34 of our state’s constitution, cities can, and typically do, block affordable housing and homeless shelters from being built in the first place.

And we absolutely need zoning reform to legalize multi-family dwellings, at all ends of the income and affordability spectrum, in neighborhoods where such housing is currently banned.

Reforms Needed to Existing Law

Though the state’s Regional Housing Needs Assessment (RHNA) requires that California communities build sufficient housing to keep up with growth, the law has been toothless: There is no enforcement mechanism in current law. Despite important enforcement mechanisms in a pending budget trailer bill, the RHNA process itself is easily gamed by opponents of housing, such as the city of Beverly Hills, which satisfied its RHNA requirements by building three low-income units over the last 8-year RHNA period.

The truth on the ground is that the entities that often propose housing for people experiencing homelessness propose their projects in residential areas that often are not zoned for multi-family housing. Because of this, they’re vulnerable to litigation from local opponents whose priority is “preserving neighborhood character,” not solving the homelessness crisis.

So while the existence of NIMBYism may be a controversial topic in the media, there’s abundant evidence that policies that empower the NIMBY mindset are a major roadblock to addressing homelessness in our state.

The Numbers Don’t Lie

The need for substantial additional housing production in the State of California has been repeatedly reinforced by numerous independent researchers in both the academic, non-profit, and private sectors. The numbers are both readily available, and stark: Between 2005 and 2014, California built only 300 new homes for every 1,000 additional households — less housing for new arrivals and immigrants than comparatively large states like New York, Texas, Washington, and Nevada. This chronic under-building has created a statewide deficit of 3.5 million homes; so, increasing the supply of housing is a fundamental need that’s central to any approach to solving the problem.

In fact, in order to maintain price stability for a growing population, California’s Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD) has estimated we need to build 180,000 homes annually. Since the 2008 Recession, California has built well under 100,000 — an all-time low in the state’s history, despite the unprecedented employment boom that’s occurred in the intervening years.

The result: The rising tide of eviction, displacement, and homelessness that’s harming residents across our state.

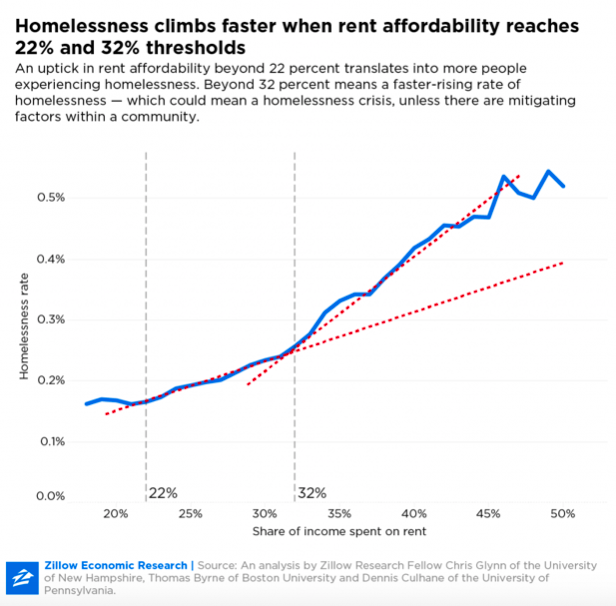

According to a report released in early June by Public Counsel and the UCLA School of Law, rapidly rising rents — the tell-tale sign of a housing shortage — have been driving landlords to evict an ever-larger share of their tenants. Additional research from the real estate platform Zillow found that homelessness begins to track upward when the share of income people spend on rent begins to exceed 30%.

Many evicted tenants are able to find new housing, though the share of income spent on rent often exceeds 40% or 50% in their new homes. But many are not so lucky. They end up leaving the state or, in a growing number of cases, on the streets.

Necessary, But Not Sufficient

Cities like Los Angeles have taken a few important steps toward addressing the growing crisis of people suffering from burdensome rents, or at risk of homelessness. The city’s Transit-Oriented Communities program (TOC), and funding for supportive housing for the homeless and housing-insecure under measure HHH, are making a dent. The problem: They’re nowhere near sufficient.

As the Los Angeles Times editorial board wrote in early June:

“The frightening news is that as fast as the county bailed people out of homelessness, more fell in. There were 3,886 veterans who were homeless in 2018. About 2,800 got housing. And yet, this year the number of veterans counted as homeless was still 3,874. There are more people living in cars, vans and RVs, and there are 17% more people in tents and makeshift shelters on the streets than were counted in 2018. Of the 14,075 ‘chronically homeless’ people on the street last year, 4,902 got housed. Yet those who remained were joined by so many more people who graduated into chronic homelessness — defined as having a disability and living on the streets for at least a year — that the overall number went up 17%.”

Sadly, leaders in too many California cities continue to promote band-aid solutions that prioritize their constituent’s aesthetic or ideological preferences over the basic human need for housing. Rent control and subsidies for low-income housing are crucial, but unless coupled with increased housing supply, are half measures that don’t address the core problem.

In March, in spite of their stated commitments to addressing the housing crisis, leaders in the City of Los Angeles passed a resolution opposing SB 50, the More HOMES Act. SB 50 would have enabled affordable housing development in many areas of LA that currently ban the construction of affordable apartments and multi-family homes.

The situation is not much better in most of California’s booming coastal cities. From San Francisco to Irvine, city councils are fighting against exactly the kinds of apartments and multi-family dwellings that give seniors, middle- and low-income workers like nurses and teachers, and college students a secure and affordable place to live.

As Elise Buik, the head of the United Way of Greater Los Angeles, told the LA Times:

“Our housing crisis is our homeless crisis. And we’ve got to get people to understand that.”

She said that people struggling with mental illness or substance abuse issues and who are living in encampments are often the most visible, but it is a myth that people experiencing homelessness decline help or prefer to live outdoors — one that contributes to misconceptions about the effectiveness of often costly services.

If We Want More Homes, We Need to Build More Homes

The bottom line is that we desperately need to build more housing — not in high-risk fire zones, and not sprawling across our farmlands and into the remote eastern deserts, but in our existing urban areas, in an infill pattern that takes advantage of cool coastal climates, high employment clusters, and easier access to jobs and services. Not only would this address our crushing housing crisis, but it would reduce air pollution and traffic, help California meet its climate goals, and help make sure that our state’s high-resource cities are affordable to everyone seeking opportunity.

Despite our setbacks with SB 50, California YIMBY is continuing to advance the bill’s various provisions, which are needed to ensure cities have the tools they need to build more homes and end the housing crisis.

Regardless of what happens in Pasadena and Palo Alto, we’re focused on the same suite of actions that housing experts up and down the state agree on: Protections for vulnerable renters and sensitive communities against demolition of, and displacement from their current homes; incentives for home builders to produce below-market-rate housing for low- and middle-income employees, like restaurant workers, teachers, and nurses; and changes to local zoning codes to legalize apartments and multi-family housing near transit and jobs.

As poll after poll has shown, these measures are more than just an urgently-needed solution to the housing crisis: They’re wildly popular with an overwhelming majority of Californians.

To get them across the finish line, we’re going to need your help. So please, join us today. We’re in this fight for the long haul — until every Californian has a secure, affordable place to call home.