What the Fee? A Closer Look at Impacts

We’re doing a “throwback Thursday” installment of The Homework to highlight some timely research published last year by UC Berkeley’s Terner Center for Housing Innovation on housing impact fees. After the 1978 passage of Proposition 13, localities began to rely more heavily on fees and other exactions from new development to cover the cost of infrastructure and service needs after property tax revenue dried up. AB 879 (Grayson) expanded reporting requirements on local housing development progress, and mandated a study on impact fees. What follows is a careful survey of 40 jurisdictions, with more detailed case studies of 10 local governments, analyzing the nature and impacts of impact fees.

Key takeaways:

- Fees vary widely and add up quickly, making financial projections difficult for developers. The report recommends more transparent fee schedules and regular reporting to help make cost estimates more predictable.

- Fee structures are charged and collected at different rates across jurisdictions, often in ways that promote sprawl and discourage multifamily affordable multifamily housing.

- There is no one standard methodology used for setting fees, and cities use different benchmarks for feasibility, which can exacerbate exclusion.

Part of what makes fees difficult to study in California is that the state’s tax incentives for funding local services have brought about a vast array of fees, with “impact fees” forming just a small subset authorized by local government police power. They can be applied to “any impact reasonably attributed to new development,” and can greatly add to the cost of new housing. But the impact of impact fees is highly variable.

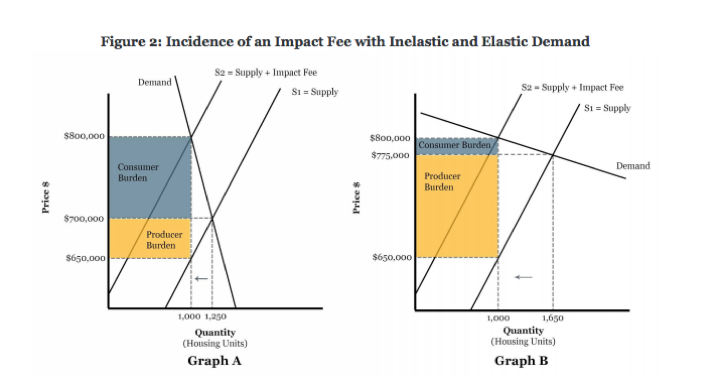

When demand is stronger, thus inelastic, and when nearby markets don’t provide an easily available substitute with lower fees, developers have more market power to pass the cost of the fees onto future homebuyers and residents, while still achieving enough return on investment to attract financing. In markets with weaker demand, or where lower fees can be substituted in a nearby jurisdiction, new development “will likely see developers and landowners pay more of the fee from their profit margin, or see a short-term drop in building as few or no developable sites meet the return requirements of developers and investors.”

This is illustrated in the following graph:

These patterns can have exclusionary effects, either reducing the availability of starter homes in an area, raising the cost of existing housing, or both. “Reducing development fees in some California localities,” the authors note,” could be expected to lower new home prices enough to significantly reduce the minimum income necessary to buy a home.”

So what does the data actually show?

First, transparency was sorely lacking. Of localities surveyed, only 28% had their nexus studies clearly available online, though these studies form the basis of those fee rates. Four of the ten case studies showed marked difficulties in publicly available fee schedules, with one only available via public records request. Only six of the forty surveyed localities posted annual reports on these fees online. This makes cost estimates increasingly difficult to produce well before shovels ever hit the ground.

Second, fees were not applied consistently in the same schedule. Some fees are charged during initial review of construction plans, while others are not imposed until after a certificate of occupancy is issued. This can result in developers encountering unexpected cost increases that jeopardize their financing.

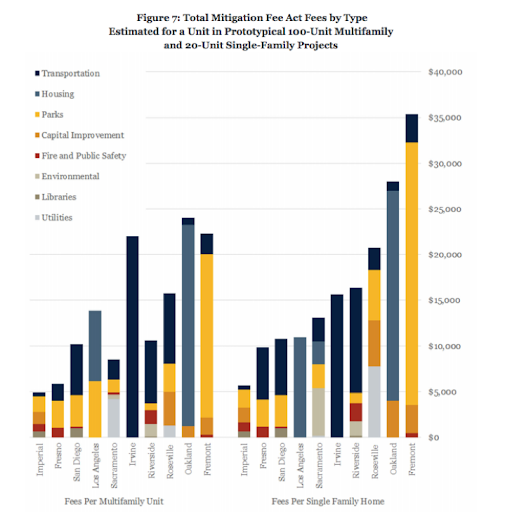

Localities surveyed had widely varying bases for setting fees. Riverside County charged on a per-unit basis, while Fremont charges their fire and public safety fees per bedroom. San Diego has forty different designated areas with different fee structures. However, the more clearly documented impact fees were, the easier they were to apply.

Third, fee structures were disproportionately higher for multifamily dwellings than single-family homes. In the ten case studies, two of the ten cities did not exempt Accessory Dwelling Units from impact fees (ADUs)—Irvine charges a full fee, while Fresno charges it as a duplex. A third, Roseville, only waives the fee for an attached ADU. Overall, though, the survey data found that fees were higher on a per-bedroom or per-square foot basis for denser housing.

“The fee multipliers chosen by localities and consultants may incentivize single-family housing over multifamily infill units, which are often more sustainable and affordable,” the report finds. Below is a chart outlining the data:

Without significant reforms to Proposition 13, this broad arsenal of fees is here to stay. But legislators need to calibrate their implementation to effectively collect revenue without discouraging homebuilding. Ultimately, the report’s various policy recommendations err on the side of clarity, uniformity, and predictability. The more our policies reflect a California that collectively takes on responsibility for housing all its residents, the more we can build a truly inclusive state for everyone.