Housing and Exclusion in Massachusetts

Why is housing more expensive in some suburban enclaves than city centers, and why isn’t subsidized housing equitably distributed? In California, we’ve been tackling these questions for years, but there is much to be learned from other states. In Massachusetts, a law known as Chapter 40B empowers a state-level board of appeals to overturn local land-use decisions that are found to disadvantage subsidized housing projects.

It’s a somewhat narrower, but statutorily powerful cousin of California’s Housing Accountability Act, which California YIMBY has worked to strengthen in recent years. A new study by Edward Goetz and Yi Wang at the University of Minnesota evaluates the program’s strengths and weaknesses.

Here are the key takeaways:

- Over the past two decades of the program’s existence, more subsidized housing has been built in Massachusetts—not a lot, but a marked increase in the statewide housing stock.

- More than half of those subsidized homes were built in the Boston metro area, but the distribution was highly inequitable.

- Cities with a greater white population saw the smallest increases of subsidized housing.

Already in the first paragraph, the authors identify a root cause of the state’s housing shortage that could have been written about California: “Exclusionary land-use policies implemented by suburban governments over decades have contributed to the spatial concentration of publicly subsidized housing in central cities and the development and preservation of affluent, racially homogeneous suburban communities.”

So how does this work in Massachusetts?

Under the Chapter 40B program, established in 1969, cities in Massachusetts are supposed to be making progress on reducing barriers to racial and economic integration. If less than 10% of a municipality’s housing stock is subsidized housing for low- and moderate-income households, the law gives the state purview over subsidized housing project proposals. Municipal governments are tasked with proving that a decision to deny permits for subsidized projects was based on a “valid health, safety, environmental, design, open space, or other local concern”—sound familiar?

Similar policies established later in Connecticut and Rhode Island were found to have increased the production of affordable housing.

The first 25 years of the Massachusetts program were relatively successful: the state’s Housing Appeals Committee (HAC) overturned 76 local permit denials. Previously, only 3 cities passed the 10% threshold; after 25 years, 23 cities passed it. Since then, the HAC has overturned fewer cases, as subsidized housing developers and local governments have entered into settlements rather than bringing permit decisions before the HAC. Goetz and Wang’s study analyzes the next two decades of 40B compliance, from 1997 to 2017. Their findings are startling.

- Hypothesis 1: municipalities with larger white populations develop a smaller share of subsidized housing.

- Hypothesis 2: richer municipalities develop a smaller share of subsidized housing than poorer ones.

- Hypothesis 3: the better fiscal state a municipality’s budget is in, the smaller its share of subsidized housing.

All three hypotheses were confirmed to some extent.

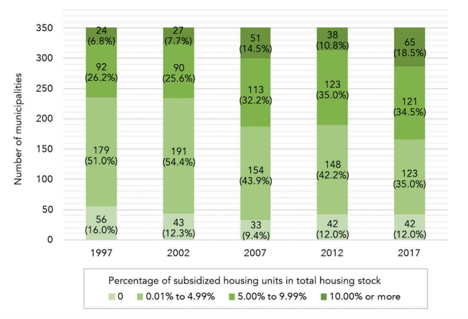

How could this be? As the graph below shows, the share of subsidized housing in the state’s housing stock has increased overall.

“There is strong evidence at the bivariate level for the racial version of the exclusionary hypothesis,” the authors note. Cities with smaller ratios of debts to expenditures, and generally better ratios of revenues to expenditures, tended to have smaller shares of subsidized housing. The evidence gets a bit trickier when it comes to wealth, since there was no strong correlation between subsidized housing and median household income, but there was a strong correlation with the poverty rate. The fewer households living below the poverty line, the less subsidized housing.

“There is strong evidence at the bivariate level for the racial version of the exclusionary hypothesis,” the authors note. Cities with smaller ratios of debts to expenditures, and generally better ratios of revenues to expenditures, tended to have smaller shares of subsidized housing. The evidence gets a bit trickier when it comes to wealth, since there was no strong correlation between subsidized housing and median household income, but there was a strong correlation with the poverty rate. The fewer households living below the poverty line, the less subsidized housing.

That may seem like a chicken-and-egg question: wouldn’t cities with more subsidized housing by definition have more households below the poverty line? Whence the exclusion? The multivariate analysis offers more clues.

Generally, the smaller the city, the smaller its relative share of subsidized housing. Across racial categories, more diverse cities saw higher shares of subsidized housing; more diverse cities were also more likely to be “high performer” cities that had met the 40B program’s 10% threshold. Curiously, wealthier cities saw lower rates of per capita subsidized housing production, but were not less likely to be high performers. “The income exclusion hypothesis is supported only for the subsidized housing per 1,000 population [metric],” the authors write, finding that “higher income communities have produced fewer subsidized units.” High-income and high wealth communities are less likely to show improvement in subsidized housing provision, but it was not so strong a predictor for their status quos.

A more troubling unintended consequence of this program is that the 10% threshold effectively absolves cities of the need to further integrate their communities past that benchmark. Indeed, the researchers found that the 10% mark had a significant “plateau” effect, as the incentive for producing more subsidized housing was lifted. The study notes that “meeting the 10% goal has a slight negative effect on subsequent gains in the relative size of the subsidized housing stock.”

What lessons do you think California can draw from these findings?