The Embarcadero Institute’s Double-Counting Report is Wrong

As cities around California contend with their latest Regional Housing Needs Assessments — a periodic assignment of housing targets mandated by state law which compels local jurisdictions to legalize the housing needed to accommodate new residents — the anti-housing activists at the Embarcadero Institute have reemerged with a new flat-Earth theory of housing in California.

California YIMBY has spent more time than we’d have liked exposing the Embarcadero Institute’s dishonest NIMBY bias , but as the old saying goes, “A lie makes it halfway around the world before the truth has put its pants on.”

And so we’re back to warn others about the latest colorful outburst from the Palo Alto- based NIMBY think-tank, whose chicanery is a stunning accusation that a mathematical error has caused California’s Department of Housing and Community Development, (HCD), to “exaggerate by more than 900,000 the units needed in SoCal, the Bay Area, and the Sacramento area.”

As a result of SB 828, a bill authored by state Sen. Scott Wiener in 2018, communities who failed to build adequate housing in previous Regional Housing Needs Assessment (RHNA) cycles would now have to make up the shortfall. In the past, these shortfalls would act to set a new, lower floor in housing goals — essentially creating an incentive for cities to miss their housing targets.

This last bit is important because in the previous RHNA cycle, just two municipalities out of 539 met their RHNA goals, according to a review done by the Los Angeles Times. This allowed whiter and wealthier communities to get away with underbuilding all types of housing, but particularly affordable housing. For instance, according to an analysis done by the state Senate, the LA-area city of Redondo Beach was allocated about 1,400 units of housing to be built over an eight year period while neighboring Hermosa Beach and Manhattan Beach were allocated just two and 37 units respectively.

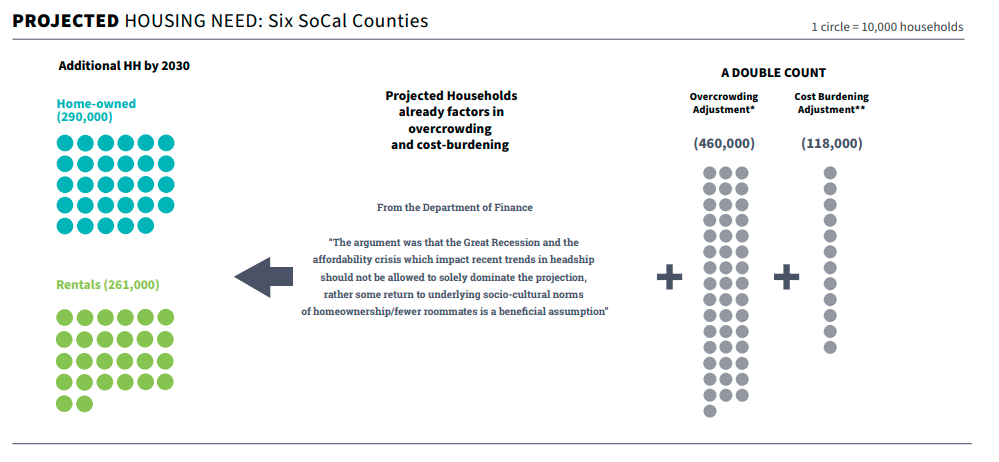

Wiener’s aim in crafting SB 828 was to force recalcitrant cities to make up for past shortfalls in future housing allocations. But according to Embarcadero Institute President and report author Gab Layton, accounting for these past deficits as required by SB 828 caused HCD to “double count” a city’s RHNA allocation. By factoring in both overcrowding and cost burdening, state officials were not redressing past underproduction, but rather creating unnecessary and erroneous new targets for municipalities to follow.

According to Layton, state officials had already accounted for cost-burdening and crowding when they projected future growth with a higher “headship rate” or roughly the ratio of households to adults in a given geography.

Double Counting in the Latest Housing Needs Assessment, Oct. 2020. Pg. 4.

Double Counting in the Latest Housing Needs Assessment, Oct. 2020. Pg. A-7.

To justify this claim, Layton cites a 2006 presentation by Paul Fassinger, Research Director at the Association of Bay Area Governments (ABAG), to that organization’s Housing Methodology Committee during planning for the 2007-2014 RHNA allocation. In the meeting minutes, a discussion broke out between Fassinger and ABAG officials about whether it was appropriate to use figures from the state of California for the Bay Area, whose headship rate would be lower due to its high cost of living, (larger households full of adults generally translate into lower headship rates.)

Fassinger responds to the group that “HCD uses these higher headship rates because the RHNA process is intended to alleviate the burdens of high housing cost and overcrowding.” Fassinger isn’t saying that the state pads the relatively straightforward calculations used to determine the headship rate, he’s saying that the purpose of the RHNA process is to create more housing such that the Bay Area would cease to be expensive and crowded. Furthermore, looking at the final numbers adopted by ABAG for that cycle show that the headship rate suggested by Fassinger was completely discarded. Rather than the 243,400 housing units suggested during that July 2006 meeting, ABAG eventually settled on just 214,500 units for that cycle.

Layton also cites the methodology notes to the California Department of Finance’s Household Projections for 2020 to 2030. However, that section doesn’t refer to any adjustment made for cost burdening or overcrowding, it speaks to the justifiable decision to average headship rates for the 2000 and 2010 census as the 2010 census captured headship rates during the middle of the Great Recession. In times of economic crisis, more adults take on roommates or move back home, leading to a lower headship rate that would bias future discussions of housing need downward. These types of adjustments are common when studying demography and housing economics.

Though UC Davis Law Professor Chris Elmendorf posted a masterful takedown of Layton’s work on Twitter shortly after its publication, the report has unfortunately made its way into the deliberations of several city councils. It was cited by Orinda Vice Mayor Dennis Fray in a March 3 council meeting, by Mission Viejo’s City Attorney in a Feb. 3 letter, by Beverly Hills City Manager George Chavez in an opposition letter challenging that city’s RHNA allocation and was the subject of a recent fight on the Los Altos City Council when two members of that council defied the majority and brought Layton in to present that report during public comment period, a possible violation of the state’s Brown Act.

It’s understandable why there’s a market for the Embarcadero Institute’s fairy tales. After all, the same dead-wrong motivated reasoning creates an ample market for climate change denial, anti-vaccination mythologies and fantasy-land stories of stolen elections and voter fraud. But while it’s one thing for the wealthy segregationists to peddle falsehoods, it’s unconscionable for duly-elected public servants to use shoddy powerpoints as justification for prolonging and exacerbating California’s housing crisis.

Elected officials must be held to higher standards — not just for the decisions they make, but for the evidence they consider before making them. California’s universities are home to some of the most eminent housing scholars in America. Before making decisions that impact the lives of thousands, perhaps they should give them a call — instead of turning to the NIMBY coloring books of the Embarcadero Institute.