The Housing Crisis Primed California’s COVID19 Tragedy

When COVID-19 began surging in California in late November, the pandemic was attacking an already sick patient.

Despite the state being an early adopter of mask-mandates and social distancing rules, California is the center of America’s COVID-19 tragedy. Between mid-December and mid-January, Los Angeles County — a region of just 10 million people — averaged about 15,000 new cases every day, roughly the same as Florida, a state of 21.5 million, according to data compiled by the New York Times. Sadly, an average of more than 200 people per day have been dying of COVID-19 related complications in California since mid December 2020.

How did a state that managed to avoid the worst of the pandemic for months end up with case counts that put it on par with states that openly shunned mask wearing and other precautions? The answer may lie in examining California’s pre-existing conditions. Just as COVID-19 can be deadlier for individuals already sickened by other maladies, so too can an entire state be more vulnerable to the pandemic based on its condition when the contagion arrived.

It’s no coincidence that California is both the epicenter of America’s COVID19 crisis and its housing crisis. California ranks just under Florida for the largest share of cost-burdened renters in the nation, with about 29 percent of the state’s renters spending more than 50 percent of their income on housing. When including the cost of housing — as the U.S. Census Bureau’s Supplemental Poverty Measure does, but its official poverty line does not — California goes from being America’s 21st poorest state to its poorest.

California’s exorbitant housing costs, brought on by decades of underbuilding, have forced many to pack more people into a housing unit than it was designed for. Crowding, defined by the U.S. Census to be more than one person per room in a given living space, is most prevalent in California, according to the Urban Institute. Crowding is especially acute in Southern California where the top nine most crowded census areas are located. Further, as reporting from CalMatters earlier this year showed, crowding particularly affects “essential workers” whose jobs don’t allow them the luxury to socially distance and who contract COVID-19 at far higher rates than those doing other jobs.

Though the COVID-19 pandemic is just about a year old, already research has emerged showing the link between crowding and its spread in the United States. This, however, should come as no surprise. The World Health Organization has long identified crowding as a catalyst for disease spread. John Snow, one of the progenitors of modern epidemiology, observed a link between household crowding and cholera deaths in his now famous 1855 study of the Broad Street pump.

In spite of this, many have drawn a false linkage between density and COVID-19 case rates. In fact, politicians have bookended the pandemic with this erroneous claim.

At the start of the pandemic, as New York City was being ravaged by the disease, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo tweeted that “There is a density level in NYC that is destructive.” Nine months later, Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti said in an interview that COVID-19 was devastating his city because “We’re the densest metro area in the United States.”

But none of the evidence supports a causative relationship between density and COVID-19 spread. Tokyo, Seoul and Taipei, all far denser than the densest American cities, had nowhere near the outbreaks that relatively sprawling American metros did.

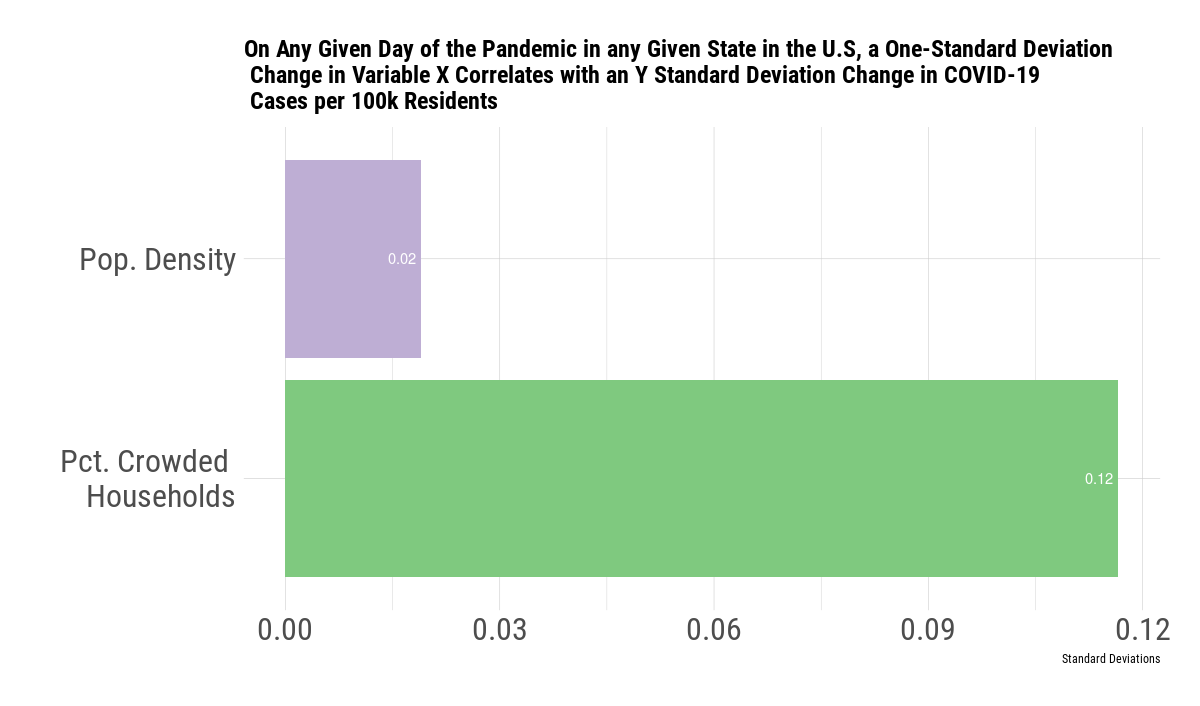

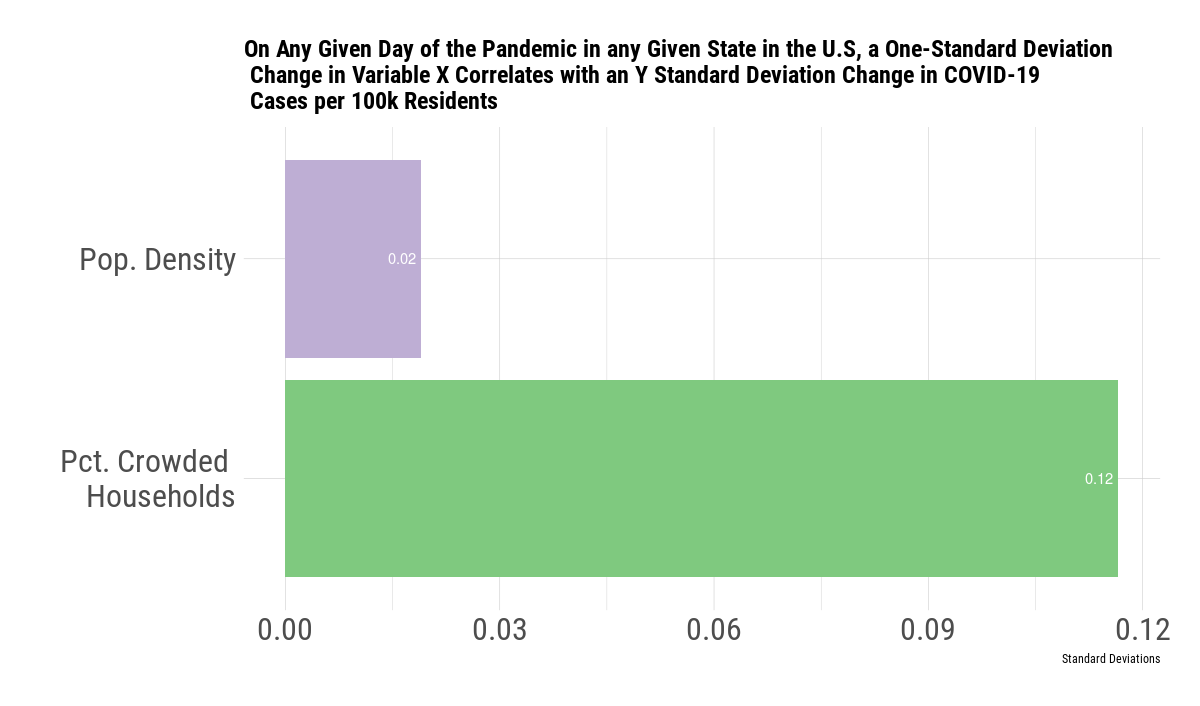

Examining the correlation between both population density and crowding on cumulative COVID-19 case rates in American counties using regression analysis, I find that in any given state on any given day of the pandemic, an increase in crowding correlates with a COVID-19 infection rate that’s about six times higher than an increase in population density. In this relatively unsophisticated model, a 2.3 percentage point increase in the crowding rate correlates with six times the effect as a change in the population density from relatively rural San Joaquin County to Santa Clara County, home to California’s 3rd largest city. These results echo a much more sophisticated June study from the Journal of the American Planning Association that found county density to be unrelated to COVID19 infection rates.

Of course, there are a myriad of other factors that drive the spread of COVID-19 in a community besides household crowding. To keep the next pandemic from being as devastating as this one, California needs to take dramatic steps to fix structural racism and increase collective bargaining power. But in the near term, the remedies to our housing crisis are both accessible and apparent. Removing local impediments to new housing in jobs-rich areas, expanding government assistance to low-income Californians, and prioritizing density near mass transit will not only make us more resilient for the next pandemic, but will better the lives of millions in innumerable ways.