The Weight of Cities – UN Report on Dense Infill Housing as Climate Solution

The United Nations has long been a strong advocate of the YIMBY policy toolkit as an integral strategy for fighting climate change. A new report from its International Resource Panel (IRP), “The Weight of Cities,” underscores the importance of new homebuilding in urban environments as a critical step we must take to reduce emissions.

Climate and housing policy present an apparent paradox: how can cities be the future of a sustainable climate if they account for 75% of global energy demand, and 60% of domestic material consumption The answer lies in us, and the way we share land together. Currently, 54 percent of the global population lives in cities—that’s projected to reach 66 percent by 2050. As it turns out, that means there is a major opportunity in cities around the world to reduce emissions: with a “suite,” or portfolio, of better urban planning policies, the IRP estimates that cities can halve their annual domestic material consumption per capita, and reduce emissions by up to 30-55%.

To achieve this, the IRP report advocates for reforming three things: (1) transportation; (2) housing; and (3) governance. We must:

- Restructure our metropolitan regions for humans first, not cars;

- Plan our urban centers for denser, more efficient living; and finally,

- Govern metropolitan planning efforts regionally.

What ties these strategies together is simply the cheaper, more efficient energy and infrastructure needs we could have by shifting from sprawl to denser living. Having plentiful amenities, jobs and housing close together for all income groups, where more people can walk, bike, and take transit, could reduce energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions “by a factor of two or more,” as could more energy-efficient new buildings.

Affordability, sustainability, and walkability all have to be addressed at once. We ought to recall, for instance, a 2019 study by Rice et al of displacement in Seattle that found larger carbon footprints for low-income households that are priced out of the urban core into car-dependent suburbs with longer commutes. And because more affluent residents have larger carbon footprints overall, Kammen et al (2018) found that wealthier households also see major emission reductions when living in denser urban areas. The UN backs up the case we’ve seen consistently backed up in research: climate-resilient cities are necessarily more integrated and diverse cities.

In a case study from Delhi, for example, the data indicates that rehabilitating outlying neighborhoods with better housing and electricity infrastructure “has a significant social impact, but relatively little overall resource impact.” In other words, as living standards increased, energy demand increased much less. As cities and countries grow, sharing resources and land more equitably is necessarily the most sustainable path forward.

Fortunately for cities, this also just makes plain old fiscal common sense: “Optimizing densities and reducing sprawl also improves the sharing of resources (e.g. shared walls and roofs in apartment blocks) and reduces the distances that need to be covered by infrastructure networks (e.g. shorter pipes), allowing for savings in the materials and costs associated with service provision.”

Fortunately for planners, the report is packed with simple best practices for structuring genuinely sustainable mixed-use neighborhoods, such as: “at least 40 percent of floor space should be allocated for economic use in any neighbourhood, and single function blocks should cover less than 10 percent of any neighbourhood.”

Planning the spaces where people live, work, consume and recreate also necessitates efficient policies for how people move between these spaces. To that end, the IRP strongly endorses Transit-Oriented Development (TOD), though emphasizes the need for a holistic approach that also emphasizes development-oriented transit, so to speak. Transit systems must be built to connect between urban centers that complement each other in “polycentric” agglomeration economies, and between urban centers and their adjacent neighborhoods. Sharing urban land and transportation infrastructure more equitably is also a strategy to “increase nearby residents’ access to the agglomeration benefits,” by sharing economic opportunity itself.

Ultimately, we face a simple choice: “2050 can either reinforce a business-as-usual paradigm of the car-oriented ‘100-mile city’ or, alternatively, promote densities and infrastructure solutions that make it possible to live a good quality of life without emitting more [greenhouse gases],” and without rapidly growing our per capita resource consumption. But these decisions must be governed in effective ways, and that means urban metropolitan regions plan at the regional level.

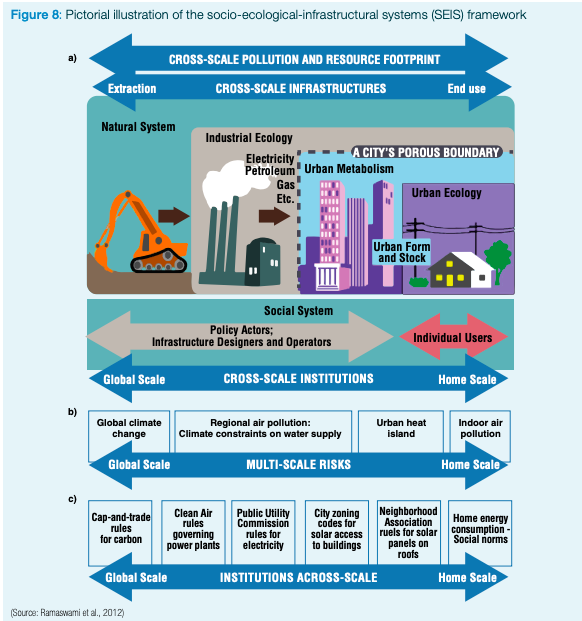

To that end, the IRP advocates for “an active and goal-setting role for the state,” working proactively with formal and informal institutions from the global to regional level to achieve positive goals. Our actions must be coordinated at the individual, local, and international level. To better share our planet, we must work together with robust democratic institutions. California YIMBY is proud to help build this movement. Will you join us?