Housing is Opportunity (Part 1)

As opportunity grows in across the metropolitan United States, tight housing supply has concentrated economic opportunity in more highly desirable neighborhoods. At first glance, that sounds redundant, doesn’t it? Not really—when UC Berkeley’s Terner Center for Housing Innovation took a closer look at the data, they found something startling: 40 percent of the nation’s high-opportunity neighborhoods remain dominated by single-family housing. And it’s not just because of sprawl in the sunbelt. Even booming job centers like the Seattle-Tacoma metro region saw a slight increase in predominantly single-family neighborhoods over the past few decades.

This is the one of two studies in a series on housing supply and opportunity, “How Housing Supply Shapes Access to Opportunity for Renters,” by Elizabeth Kneeborne and Mark Trainer. The other half of this series, which we’ll cover next, addresses homeownership. The big takeaways for renters:

- Single-family neighborhoods in the nation’s largest metro areas have increased by almost 40 percent since 1990, “largely at the expense of neighborhoods that offer a more diverse mix of housing types.”

- As opportunity grows in cities, some neighborhoods have become more restrictive in their housing supply. 25 percent of neighborhoods that had more mixed housing stock in 1990 became predominantly single-family by 2016.

- Opportunity and density have effectively been bifurcated. New construction of affordable housing has been largely concentrated in denser neighborhoods, but when built in Single-Family tracts, it has improved neighborhood conditions for subsidized residents.

By now, you may have noticed a pattern in The Homework newsletter: we at California YIMBY aren’t making this stuff up. Time and again, evidence shows that restricting housing construction to low-density, single-family homes in affluent, high-opportunity neighborhoods hurts economic mobility, and makes our society more unequal. It’s time to reverse this trend.

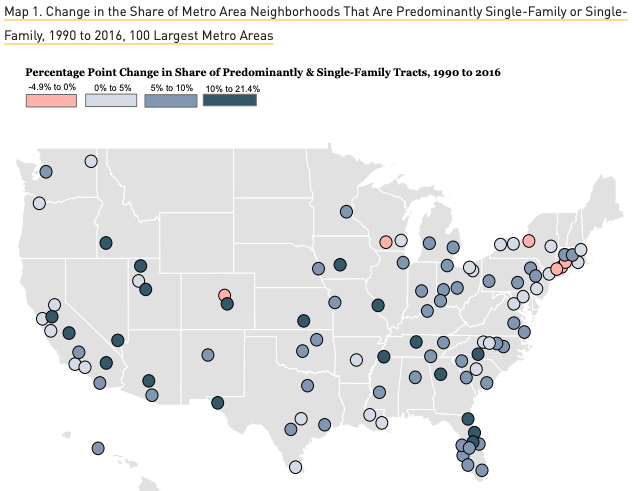

First, in a just and equitable society, you would expect to see growth in metro areas to correlate with density, not sprawl. But unless you’ve been living under a rock, you’re well aware by now that the United States has subsidized sprawl and white flight at the expense of more diverse, productive, and ecologically sustainable urban metros. So it’s not surprise that most of the country’s biggest cities have seen an increase in predominantly single-family neighborhoods, but it’s nice to see it mapped out. Here’s what that looks like:

“By 2016,” Kneeborne and Trainer note, “Predominantly Single-Family and Single-Family neighborhoods made up the majority of neighborhoods in 73 major metro areas across the country.

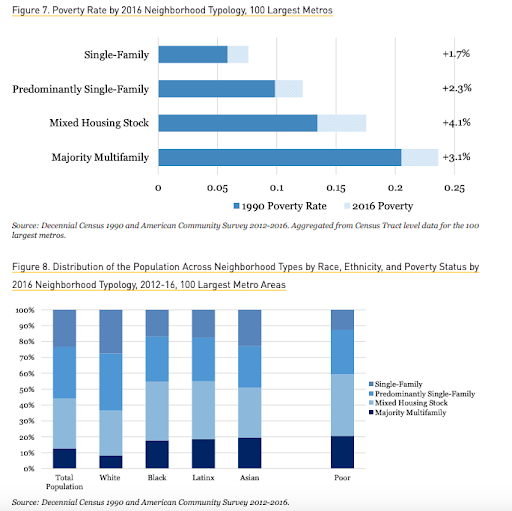

What does this mean for American renters? New rental housing has largely been built further from the highest-opportunity neighborhoods in these major metro regions. Consequently, rents are higher in single-family neighborhoods that have much less rental stock, and these neighborhoods are more segregated. Poverty is lower in single-family neighborhoods, and the population is whiter. Here’s what that looks like:

There’s an additional, surprising wrinkle in the data: renters in single-family homes are largely not finding these housing opportunities in neighborhoods with overall greater economic opportunity. In other words, even single-family rentals are in poorer neighborhoods than single-family housing overall. “The data suggest that the more concentrated single-family rentals become—regardless of neighborhood type—the less likely they are to be located in areas of opportunity,” the authors say. “Thehigher the concentration of single-family rentals, the less opportunity-rich the neighborhood tends to be.”

So far, this has largely covered renters scrambling for opportunity on the private market. What about renters accessing subsidized housing? There, too, Kneeborne and Trainer found troubling patterns of segregation and inequality.

Considering that the Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) is the most widespread financing tool for affordable housing in the United States today, it is not entirely unexpected to see most subsidized housing projects since 1990 in the form of higher-density construction—74 units on average. But as we have just seen, density has become negatively correlated with wealth and opportunity, so more affordable housing has been added in neighborhoods where residents are more likely to stay poor.

From 1990 to 2016, neighborhoods with predominantly multi-family housing accounted for only 8 percent of housing supply growth in the nation’s largest 100 metro areas, but 25 percent of all new LIHTC projects. That proportion is completely reversed for single-family neighborhoods, which accounted for 20 percent of overall housing growth in the same period, but just 8 percent of new LIHTC projects.

The reasons for these disparities sound familiar to anyone with a cursory knowledge of American segregation—i.e. racism and classism—but the fears of affluent residents that new neighbors in subsidized housing will degrade the quality of the area are entirely unfounded. In contrast, residents in the rare LIHTC projects that do get built in wealthier, largely single-family neighborhoods enjoy tremendous economic benefits.

Neighborhoods that added more LIHTC projects had higher rates of poverty and lower educational attainment rates than neighborhoods that added less. Conversely: “Single-Family neighborhoods containing LIHTC units exhibit higher opportunity characteristics than all other neighborhood types, regardless of their LIHTC presence.”

In response to these trends, the Terner Center presents some key recommendations:

- Expand the availability of tenant-based subsidies, and remove the barriers to their use.

- Reduce barriers to new production in high-opportunity neighborhoods.

- Allow more flexibility for new LIHTC projects and acknowledge the higher costs of development in high-opportunity neighborhoods. (In other words, building affordable housing in wealthier neighborhoods costs more, but it’s worth it.)

- Scale up other innovative sources of financing for new affordable construction.

Sounds great! Let’s get to work.