Institutional Investors in California Housing Markets

TL;DR:

Following the Global Financial Crisis of 2007-2008, large institutional investors, such as the private equity firm Blackstone, purchased foreclosed homes in distressed neighborhoods throughout the country. Many of these neighborhoods were the same historically Black and Latino neighborhoods that were targeted for high-risk, subprime loans by unscrupulous lenders just a few years prior.

Just over ten years later, how prevalent are institutional investors in California neighborhoods? A review of scholarship around the issue shows their presence in California communities is marginal at best. However, these investors intentionally sought out housing markets with high-demand, but constraints on new development — a condition that describes much of urban California. The studies reviewed here focused primarily on the impacts of institutional investors on the rental market and future blog posts will explore their impact on homeownership and the home sales market.

These findings imply that removing constraints on housing supply would help limit the presence and influence of institutional investors, whose goals often do not align with the priorities of affordability, housing security, and neighborhood integration.

The Problem

Is California being taken over by corporate landlords? And if the state makes it easier to build new homes, will it simply be inviting more corporate landlords, and worsening rather than improving affordability?

Concerns of this sort are common. In 2017, when the California legislature first considered a bill intended to loosen zoning and dramatically increase housing development statewide, Zev Yaroslavsky, a prominent Los Angeles politician was quoted as saying “This bill is not about YIMBYs vs. NIMBYs; it’s about WIMBY’s: Wall Street in My Backyard.”

According to this narrative, new development allows a new sort of real estate investor to come to California’s communities. Motivated by a rapacious desire for high returns, these new investors will increase rents, increase evictions, and reduce affordability. Invitation Homes, the former real estate division of the private equity firm Blackstone, is the poster child of this worry.

There is no question that following the Great Recession, big financial firms–Blackstone among them– entered the real estate market in an unprecedented way. Many people lost their homes during the Recession: over 2.3 million homes were foreclosed in 2008 alone. Those who lost their homes to foreclosure were disproportionately Black and Latino and all communities of color were more likely to encounter foreclosure than whites[1].

Into the resulting chasm of housing demand stepped many “institutional investors,” another name for private equity, hedge funds and other large financial players, who spent a combined $36 billion buying more than 200,000 homes across the country. These firms primarily purchased detached single-family homes, and unlike more conventional “flippers” did not resell those homes within a year or two. Instead they bought them and began renting them out, waiting for them to regain their value as the country recovered from the recession.

As one Urban Studies professor told the New York Times, “During one of the greatest recoveries of land value in the history of the country, from 2010 and 2011 at the bottom of the crisis to now, we’ve seen huge gains in property values, especially in suburbs, and instead of that accruing to many moderate-income and middle-income homeowners, many of whom were pushed out of the homeownership market during the crisis, that land value has accrued to these big companies and their shareholders.”

The concern about institutional investors is a reasonable one, and by now there is little doubt that in 2008 the national government should have acted more aggressively to protect homeowners from foreclosure. But the relevant questions today are whether large institutional investors are actually causing problems for today’s housing consumers, and if so what can be done about them?

How Widespread are Institutional Investors in California?

There’s no publicly available dataset of institutional investors in California housing markets so the exact scope of their investment remains a mystery. AB 354, a 2018 bill aimed at creating a statewide registry of such owners, was vetoed by Gov. Jerry Brown. As these groups operate under a panoply of names, there’s no easy method to measure their penetration in various California cities. Assemblymember Mike Gipson (D-Carson) recently introduced legislation that would create a similar registry, as well as introduce an new tax on such properties that would fund renter assistance programs.

Further complicating matters is the fact that not all corporate ownership indicates ownership by a large institutional investor. A recent report on ownership patterns in Los Angeles, for example, reviewed county assessor data and classified any property listed under corporate ownership (e.g. an LLC or Trust) as owned by “institutional investors.” The report concluded that, as a low estimate, 67 percent of the city’s housing units were institutionally owned. Since only 64 percent of LA’s housing units are rentals, the implications were that all the city’s rental units, as well as some of its owner-occupied units, are owned by institutional investors — an assertion that’s implausible on its face.

More likely, many homeowners, especially older owners whose homes have become very valuable, have followed the advice of a financial planner and placed their house in a revocable trust, which protects properties from probate and makes it easier for their children to inherit. Many smaller landlords are also incorporated as LLCs for tax or legal purposes. Strictly speaking, these moves create “corporate” ownership, but they do not suggest the presence of Wall Street firms.

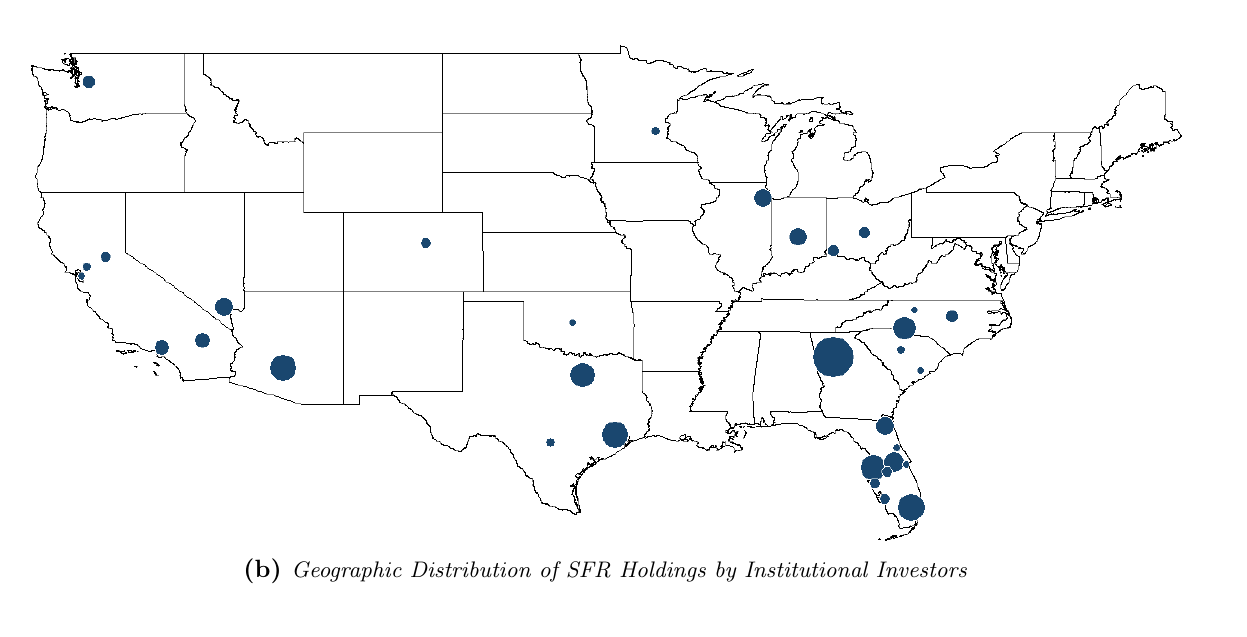

Two recent academic papers have attempted to find a more reasonable estimate of the share of homes purchased by these institutional investors after following the Great Recession. Emory University’s Rohan Ganduri and coauthors[2] found that the bulk of institutional investor purchases of single-family homes to repurpose for the rental market took place in the Southeast–particularly Florida, which was especially hard hit by the foreclosure crisis, (Figure 1.) For instance, the Atlanta metro area had about 29,000 homes purchased by institutional investors to convert into rentals, while the Riverside and Los Angeles metro areas combined had only about 8,000. Meanwhile, Sacramento, Vallejo and San Francisco had about 5,000 combined across all these metro areas. To give these numbers some context, Atlanta has 235,000 renters, Los Angeles has 2.3 million renters and San Francisco has 478,000–meaning these institutional investors own just a small fraction of the total rental housing stock.

Single-Family homes purchased by institutional investors and converted into rentals. From Gandiuri et al. (2020).

A second study [3] used similar methods and found a similar distribution of institutional investors across the country. This study reveals and the below figures show that institutional investors followed a bimodal purchasing strategy — buying up homes in both wealthier neighborhoods and in lower-income communities and communities of color. In Southern California, for example, investors purchased heavily in upscale coastal Orange County and in West LA, but also in less-advantaged parts of South LA, along the I-110 corridor south of Downtown Los Angeles. In the San Francisco Bay Area, similarly, investment rose in both wealthy urban San Francisco and the lower-income communities of West Oakland and Richmond.

The spread of institutional investors in the Los Angeles and San Francisco areas. From Lambie-Hanson et al. (2019).

Costs and Benefits of Institutional Investors

Do institutional investors raise prices? Lambie-Hanson et al (2019) do not find evidence that increased purchasing by institutional investors results in increased rents or eviction rates. However, the authors warn that their data only extends until 2014 and that results following this year are still unknown. This is important because contemporary accounts in the news media document predatory practices by these companies, specifically in rental markets[4].

Carlos Garriga and coauthors from the St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank[5] find similar results, though their analysis goes a step further. Analyzing 85 million transactions across the United States, they show that initially, institutional investors did crowd the market and worsened affordability at the lower-end of the market. However, what followed in some markets was an increase in housing production that erased these short-term gains in about six years — but only in metro areas where “there are loose supply restrictions,” i.e. ones where state and local governments don’t create impediments to new housing construction.

Finally, the University of Oregon’s Jiabin Wu and coauthors[6] offer empirical evidence in the debate over whether institutional investors leverage their market power to extract more rent out of tenants, or use their large-scale resources to enhance the quality of their rentals relative to smaller landlords. They find mixed results. When large institutional investors merge and consolidate holdings, rents in affected neighborhoods increase by about one percent. They also find that neighborhoods affected by these mergers also see significant declines in crime rates that cannot be explained by other factors such as gentrification or demographic shifts. The authors attribute the latter finding to be evidence that institutional investors offer better services than so-called mom-and-pop landlords such as enhanced security, better lighting and better screening of prospective tenants.

What Can California Do?

Ultimately, these institutional investors enter housing markets in search of profit. As Jenny Schuetz of the Brookings Institution notes, “In places where regulation limits new apartment construction, acquiring existing buildings is less risky than trying to build new rental housing[7].” These investors target markets like those in California because they can acquire a scarce asset with relatively inelastic demand — a sure recipe for profit.

Removing obstacles to new housing construction curbs the market power of these firms by introducing new competition to tight markets. In turn, these markets become less attractive to these investors; in the event they do make purchases, the deleterious effects of these purchases will be dampened.

Finally, California can do more to track these types of investors and create registries such that tenants can report and more easily sue the more abusive of these corporate landlords. As all the research reviewed for this report noted, it is extremely laborious and difficult even for academics to track the ownership of some of these purchasers. The state could fill this void so that it’d be easier to identify and penalize bad landlords.

However, an important reform California could pursue in order to mitigate any negative impacts of private equity in its housing market is to simply dilute their market share. As Invitation Homes’ own SEC filing states:

“We invest in markets that we expect will exhibit lower new supply, stronger job and household formation growth and superior [net operating income] growth relative to the broader U.S. housing and rental market.”

Institutional investors target markets with strict controls on new construction because their ready access to capital allows them to purchase a scarce commodity and become de facto monopolists. Allowing for greater housing supply in California communities would blunt the price-setting power of firms like Invitation Homes.

[1] Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Carlos Garriga, Lowell R. Ricketts, and Don Schlagenhauf. 2017. “The Homeownership Experience of Minorities During the Great Recession.” Review 99(1): 139–67.

[2] Ganduri, Rohan, Steven Chong Xiao, and Serena Wenjing Xiao. “Tracing the Source of Liquidity for Distressed Housing Markets.” Working Paper. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3324008

[3] Lambie-Hanson, Lauren, Wenli Li, and Michael Slonkosky. 2019. Institutional Investors and the U.S. Housing Recovery. Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia. Working paper (Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia). https://www.philadelphiafed.org/-/media/research-and-data/publications/working-papers/2019/wp19-45.pdf (October 24, 2020).

Mari, F., 2020. “A $60 Billion Housing Grab By Wall Street.” Nytimes.com. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/04/magazine/wall-street-landlords.html

Semuels, A., 2020. “When Wall Street Is Your Landlord.” The Atlantic. Available at: https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2019/02/single-family-landlords-wall-street/582394/.

[5] Garriga, Carlos, Pedro Gete, and Athena Tsouderou. 2019. “Investors and Housing A¤ordability.” Working Paper. https://research.stlouisfed.org/wp/more/2020-047

[6] Wu, Jiabin, Steven Chong Xiao, and Serena Wenjing Xiao. 2020. “Do Wall Street Landlords Undermine Renters’ Welfare?” Working Paper. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3410281